MOOSE HUNT

My first trip to Kodiak Alaska was for an Elk hunt with Gary “Rappid” Ryan. Kodiak is not a likely place to go Elk hunting, (since there were none on the island) but there was a herd located on nearby Afognak Island and the two-weeks we spent on Afognak is a story in itself,

but to make it short “No Elk!”

After our return to Kodiak from our elk hunt Rappid and I were sitting around the house visiting with Harold “Jake” Jacobson, (Rappid’s long time friend and room mate) and Clint “Cyclone Genesis” Simpson (their good friend and co-worker from the Weather Service Office on Kodiak). We were discussing our recent trip and other past hunting experiences some successful some not. Out of the blue Jake turned to me and asked, “Do you want to go Moose hunting?” This took me by surprise (thinking he must be joking) I said, “Sure?” Expecting a somewhat less than serious come back, but instead he asked Rappid if he would cover his mid shift that night to allow this hunting trip. To which Rappid was sport enough to say,” Yes” for my sake. Mid-shift is like a swing shift at the Weather Service Office, and it puts Gary working long hours having to cover his own shift also.

Jake and Clint scrambled “GoGet’em Airways” which is a moniker for the duo’s flying service that only existed in their conversations and on the door to their revetment (scrawled with a magic marker). They have been on several hunting trips like this one, taking friends out on a hunt to “GO GET’EM!” Jake flew a Super Cub which is a typical high wing tail-dragger often used by the bush pilots in Alaska. Clint had a Cessna 150, which was one of the most popular two-seat planes ever built. Both equipped with “Tundra tires” (large balloon type tires) designed for landing on less than smooth surfaces.

It wasn’t long and we were flying out of Kodiak with no more preparation than I would have taken for an afternoon drive, (looking for deer) back in Utah. We flew North East, across Shelikof Straight from Kodiak to the Alaska Peninsula. I don’t know if Jake had a plan where to go, or if he was just “winging it”, so to speak? We had decided earlier that any bull was game, not specifically looking for a trophy, but what ever we might be lucky enough to find.

We were flying along the Douglas River drainage, which is a tangle of streams making their way through the gravel bars of a wide riverbed. We had flown over many smaller streams visible from the air, which were rich in colors of various shades Greens, Blues, and even pinks. It seemed obvious to me that the area was rich in minerals, especially copper, which the green hues always bring to my mind, and green seemed to be the most prevalent shade. We had spotted several Bears from the air, Goats, and other game, which was interesting, but not what we were after this day.

In 1973 it was still common practice to spot game from the air, then land to harvest it. However, this method of hunting became unlawful a couple years later, with a new ruling that you could not fly and hunt in the same day. Times change and even hunting along the Douglas River drainage became unlawful when the area was consumed as part of the vast and growing Katmai National Park.

The first moose we saw happen to be a bull. It had a large enough rack that it could be easily seen from the air, so not only had we found a bull, but it’s a nice one too!

This bull was grazing at the edge of a large meadow, and stood out as if it were in a grassy field. This was edged by taller brush; and there was a tall dead tree towering from the brush, which looked to be within 50 yards of the bull. This tree towered above all else for miles around. So, we figured it would be easy to locate the tree, and then find the bull. The gravel bars along the river offered the best landing possibilities, so it was critical that the animal was within packing distance to the river, and this bull looked to be so.

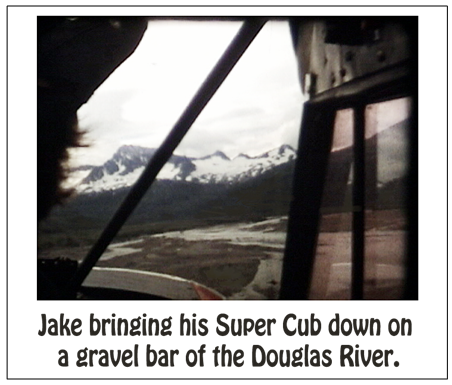

Now the experience of the pilot becomes critical, he has to make sure the gravel bar he picks is long enough and free enough from obstacles to land and get stopped, plus consider if it is long enough for take-off with possibly a heavy load.

Then there is always the question of how solid is the ground I am going to land on? Flying by nature has its risks, but when landing and taking off from unfamiliar areas, those risks are greatly multiplied. Jake picked a gravel bar, as close to the bank as possible, on the side, which the moose was located. He then performed a “Touch ‘n Go” which is a practice landing, he put the wheels of the airplane on the ground, but only to get a “feel” for it, then powered back up into the air without committing to a landing. This maneuver allows the pilot to judge how solid the ground is, wind direction, etc. The second time around he touched the airplane down, and then cleared Clint for landing. The smaller 150, which Clint was flying, would take more room to get back up off the ground, and evaluating the strip from the ground was a good idea before committing both planes to a landing. Once both planes were safely on the ground, we packed only enough gear to kill a moose, (a rifle and a knife) and it seemed as if it should be a pretty easy task from here. The tall tree was about a quarter of a mile away, yet easily visible from the gravel bar where we stood. It was slightly up hill from us, and it didn’t look that there would be any problem keeping track of it, but we could not see the moose because of the tall brush along the bank of the river.

The riverbed was over 200 yards wide at this location, and consisted of a braid work of streams weaving around the multitude of various sized gravel bars. If the water had been confined to one channel it could surely have been called a river, but as it was, the only stream between the main bank and us wasn’t much more than knee deep. Once we crossed to the main bank, we realized that the Alder brush was tall and thick, not something that had been obvious from the air. It towered over us by several feet, and the canopy was so thick that most of the time you couldn’t even see the sky.

The only available passage through this tall thick brush was the bear tunnels, which had been maintained through years of use. These trails would follow the small tributaries filtering down to the river; the Salmon were plentiful this time of year, and some of the remains of these fish had been recently abandoned, (still wet with blood) on the bank of the small stream we were following. We knew we were disturbing at least one of the feeding bears, as we moved through these shadowy tunnels. Jake assured me that in most cases a bear will go to any length to avoid contact with a human. Of course, (he added) the exceptions are the ones the folks read about back home.

We wandered in the depth of this jungle for over an hour, we figured that we were in the vicinity of the tree, but there was no way to see it through the thick canopy of Alder brush. We had stopped to rest, and were discussing a plan to go back down to the gravel bar, get our bearings on the tree and try again. Then Clint said, “Here’s the tree, I am leaning against it!” If you find that hard to believe, you should have seen the look on our faces? The trunk was huge, several feet around, with vine covered thick bark that dwarfed the alder brush towering over us. You would think something of this size would be obvious to those “looking for it” but it blended in better than a sniper in a Ghillie Suit. We had been standing at the base of this tree for several minutes now; discussing our plans in such loud voices that we were sure the moose must be in another drainage by now.

We headed toward the edge of the Alder brush, but after our recent revelation with the tree, I don’t know if any of us felt confident we could find our way out to the grassy meadow, but we did.

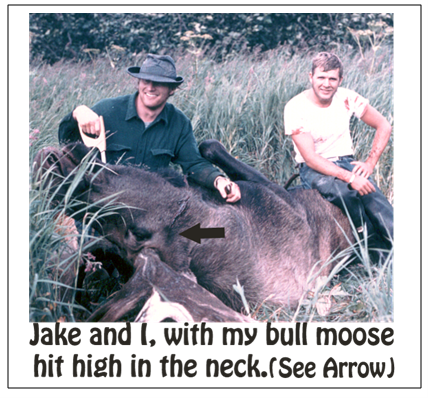

Rather than a grassy meadow, it was waist high clump grass, (another deception from the air). Even more to our surprise, was the fact that the moose had not vacated the area, it had only moved a couple hundred yards up hill and was browsing on the brush with his back towards us. Jake suggested that we should stalk closer, which we did. We were within 100 yards when the moose turned and began to walk broadside to us, and Jake told me, “Take him!”

I was packing my dad’s 300 Savage, the only rifle I had ever used for big game hunting to that time, but Big Game Hunting to me was mule deer back in Utah. I didn’t have a clue, (at the time) but I was packing a pea-shooter when it comes to hunting Moose. Not realizing that, I aimed for a neck shot, figuring two things: 1) a neck shot would put him down, and 2) his neck seemed too large of a target to miss.

I took aim with a deep breath then excelled, then took in a half a breath and held it, however even my army training didn’t seem to help steady the rifle in my excitement, but I had to make my shot so I did. The moose began taking long strides, not so much a run, but covering a lot of ground with those long steps. I counted them as he moved through the grass, I was so sure of my shot that I didn’t even cycle another round into the chamber, (Dad’s 300 Savage was a lever action). I just watched the moose, waiting for him to drop…. “Four, Five, six…” long strides before it fell. It took until about the fifth stride before the thought had even crossed my mind, “what if I had actually missed?” Jake had been wondering the same thing, (as he told me later). Jake was packing a 30.06, mostly to discourage Bears, but he did say, “…if that moose had of taken one more step, I was going to shoot!”. Which I am glad didn’t happen.

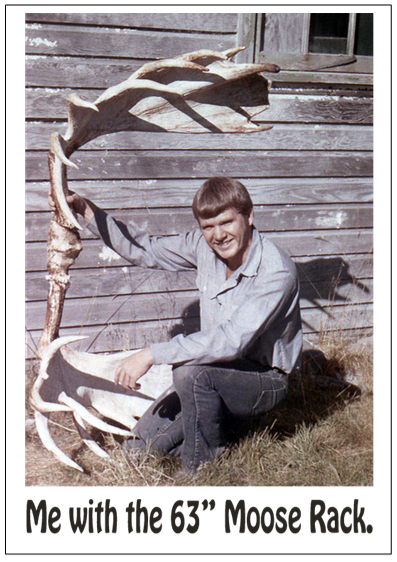

Now the work begins: You would think, being the photographer I am, that I would have some pictures of dad’s 300 Savage dwarfed by the 63” spread of this magnificent bull. I don’t.

Those cover photos you see with a trophy Bull Moose nicely posed with its knees neatly folded up underneath, are taken for people paying a lot of money for the hunt. Or possibly, someone lucky enough to have the animal at least fall in the upright position, (like Rappid). I say “Lucky”? Well, considering you would then have to turn him completely over to clean, maybe the word lucky is a misnomer. At any rate, it was a major effort for the three of us to just get this large bull from his side on to his back for the cleaning process. Jake is a big fellow off a farm in Northern Minnesota, and is well known for his strength at the base gym, and around the town of Kodiak. Clint and I are not unfamiliar to hard work, but turning a moose one way for photos and another way to clean is something that didn’t cross our minds. Besides, pictures were not what this trip was all about, I was on an Alaskan moose hunt and meat is the expected result of that.

It was an interesting thing that we could not find where I had actually hit the moose with my shot? We checked the neck carefully, but there was no sign of a hit, and none of us believed that I could scare a moose to death with a 300 Savage? It wasn’t until after the cleaning process that we realized I had hit him real high in the neck, (some folks might say in the head) but that would suggest I missed, and I don’t ever recall missing with dad’s rifle, (see insert). Cleaning a large moose is quite a chore, and this was my first experience at it. I really got in to my work you might say, because like with all the deer I had cleaned back in Utah, I wanted to remove the windpipe. This procedure only provided Jake and Clint with a few good laughs, me not realizing the futility of climbing up inside the chest cavity of this critter, them knowing we were going to be butchering it on the spot.

Once it was cleaned and cooling, we went back to the planes for Backpacks, a sharpening stone and the meat saw. Oh, and also a camera, almost as if it were an afterthought. It was about a quarter of a mile hike from the planes to the moose, (uphill, but mostly across the open clump grass) and we cleared a trail the best we could, knowing we would be making this trip several times.

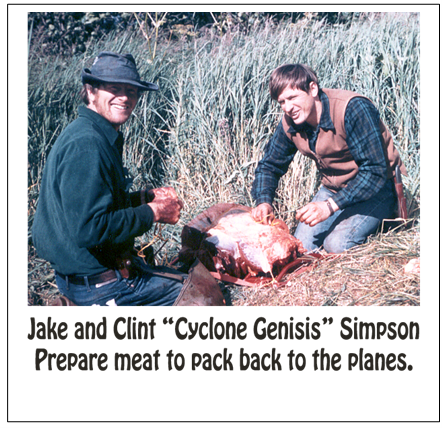

Jake knew how to take care of large game animals in the field, it was obvious he had done this before, and his skills were invaluable to us. We all helped skin the moose as it lay on its back, spreading the hide out like a huge tablecloth as we went. This provided a large clean surface to butcher the rest of the meat upon. Jake did the butchering work, cutting or sawing (as required) large chunks of meat, yet small enough they could be secured to our packs.

Clint and I made several trips to the planes packing meat, while Jake continued his butchering operation. It was late afternoon (around 6:00 pm) before we started to consider how much meat we had to fly out and how much more there was to carry. Jake had it all butchered, but there was too much meat to take out in one trip (even for two planes). So, it was discussed and agreed that I would stay behind to finish hauling down the rest of the meat, and they would take what they had and come back for me in the morning.

We loaded the planes with as much meat as they could safely take off with, and I was left behind with a one-man survival tent, two 5-gallon cans of “Avgas” (aviation fuel), some matches, my rifle, and their best wishes. Oh, and a mountain of moose meat still up on the hill that I had to get down before dark.

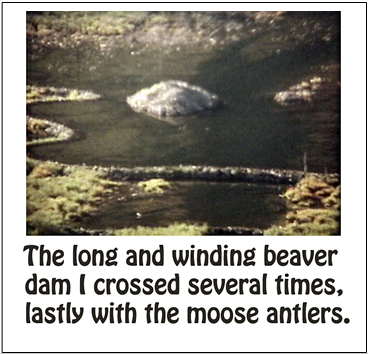

As I watched both heavily loaded planes take off and disappear over the horizon, (I got a feeling of what it is like to really be alone) but there wasn’t time to lament the situation. My work was cut out for me, (literally) and waiting up on the hill. It would take the better part of an hour to make the round trip from the kill site to the gravel bar; although the trail was pretty well worn it still had some obstacles of downed logs, tangled brush, and a large beaver dam to cross.

I became tired of packing my rifle back and forth the full distance, so I would leave it some 50 yards away from the kill, making the trip down and back un-armed, then I would pick up my rifle to approach the kill site, just incase a bear or wolf might think to move in on it while I was away. Remember that this was a time in which I was still under the impression that my rifle could kill anything; however, if a Brown Bear had claimed my kill, (on one of these return trips) I would have made better use of dad’s 300 savage as a walking stick, and walked myself out’a there!

The last trip up to the kill site was for the hide and antlers, but my extended day light hours of the North Country were growing thin; “thinner than the skin on a Moose’s nose!”

Only a Taxidermist could appreciate that last comment, because I had planned to cape out the head to make a full shoulder mount of this fine trophy. However, the skinning process is so delicate along the nose that the process was taking more light than I had left, so out came the meat saw and I just sawed the set of antlers off of the skull.

I had also enjoyed the comfort of a large moose hide bed spread in a guest room where I had stayed. The weight was somehow, warmingly-cool to sleep under, and now I had a very large one of my own! I don’t know what the weight of the hide was, but I could not pick it up, and the fact that it was like handling a bag of jello, made it impossible to handle by myself. Disappointed in having to leave the cape, and now the hide, I secured the antlers to my backpack. The antlers (in velvet) weighed 50 pounds, (and them being nearly as wide as I am tall) allowed them to pretty much take me anywhere they wanted to go. There was no way I could have packed the hide and antlers down in one trip, so it was just as well the way it turned out.

Crossing the Beaver Dam with antlers balanced on my back and rifle in hand, was an interesting part of the last trip down. The Dam was about 50 yards across, (only a foot or so wide in places) and a dozen feet of crystal-clear water to the bottom on one side and as much air to the base of the dam on the other. I had more than one close call already in crossing, and I had it figured that the water side would be better to fall into if I had to choose. It would probably be less damaging, unless I drowned? I carefully picked my way across that dam, and in spite of it all, I made it back to the gravel bar with all the meat, the antlers, and still enough twilight to quickly gather some firewood.

I hastily heaped up as much wood from along the gravel bar as I could, (luckily there was plenty available) and as I worked on my pile of wood for the night, it started to take the form of a fence? This was a marvel idea, so I continued gathering wood even past the point of need and past the point of light. Once it did get dark, I took a break long enough to build a fire and lay out my shelter. The easy pickings close to my camp were gone, so I would make my way down the gravel bar in the dark, (able to make out larger sticks and logs) and I would collect them, if I could drag them. When I quit, the fence was about four feet high and stretched about half way around the perimeter of my camp. An added bonus was that I had cleaned up the landing strip some too.

I placed the two metal Avgas cans opposite my tent across the fire, (not close) but hoping to gain a reflection, giving the look of a larger than actual fire (it worked for me). I also kept “a cup” of Avgas close at hand (but not too close to the fire). I planned to throw this cup of gas on dying embers, for a quick flare up at a time I might need it, which I hoped would not come. Worst case, I would even throw it on a bear given the need, hoping to send him over the mountain, flames included.

The night was clear with no moon, and the temperature was in the forties. I had thoughtfully placed my camp well away from the mountain of Moose meat, which accompanied me on the island. I didn’t so much care if a bear (or any other critters) ate the whole pile of meat, (Antlers ‘n all!) as long as they left me alone. The fire was going nicely now and there wasn’t much else to do but try and enjoy it.

As I pondered this wonderful glowing friend I noticed colors within the flames, I really didn’t think this as unique or odd, maybe a little fascinating, but I was in need of some entertainment (to keep my mind off of the night) and this was helping. I do recall (what seems now as a silly thought) when Rappid and I shared a fire we would always, somehow or other, find a bear’s head glowing in the embers. I was hoping not to see one tonight, and the dancing of the colors seemed to take my mind off looking so intensely for one, (least ways within the fire) and I did enjoy the flame.

It was a night ‘interrupted by sleep’, (best I can explain it) I would awake with a jolt whenever I found myself asleep or even close to it. I would then build the fire back up, and each time I did, the colors would come back even more vivid than before. At one point I could see the colors dancing off the reflections in the Avgas cans, and as Bears Butt would tell it . . . “Dancing off the Sky!”

I had no way of knowing on this dark night what was lurking along the Aleutians to the west, but Rappid was aware of it, and he was watching it with as much interest as I was watching my fire.

To the West was something maybe more threatening than a wild critter wandering into my camp, because Weather Stations along the Aleutian Chain were tracking and reporting a large low-pressure system moving up the peninsula (a storm). Rappid knew if it reached me that I could be stranded there for days. I often wonder what the outcome of that scenario might have been? I certainly would not have starved to death, but it was a scenario my mind was not prepared for, and therefore never crossed.

Light still comes early this time of year up north, and I appreciated it on this day a little more than any other. By 0600, the sun shown brightly and I had no clue of any imminent danger of a storm to the west, but the morning dragged on all the same, and my thoughts became more of, “…can they find me again?” Here I am on a small gravel bar within millions of acres of uninhabited Alaskan Peninsula. The Katmai National Park (which includes the Douglas River now) encompasses over four million acres of wilderness. And this morning, maybe not the most alone I have ever felt, but likely the most alone I have ever been.

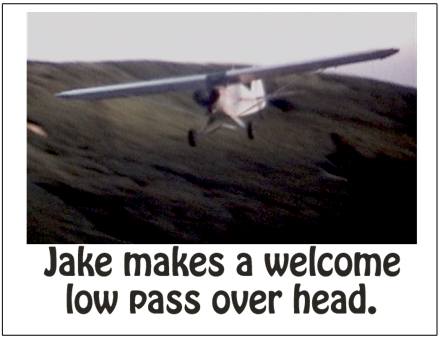

When I first thought I could imagine the distant hum from an airplane engine, it could have just as easily been the winds blowing through the tall Alder brush along the river bank, from an oncoming storm. Given time and concentration, this was no wind. It wasn’t long before I could see the faint glimmer of the sun’s rays reflecting off of a speck low over the horizon. To my eyes, it may as well have been the United States Cavalry with their bugle sounding and the stars and stripes flapping high overhead, the definite drone of an airplane engine was music to my ears. When I could identify it as Jake’s plane, I don’t ever recall such a feeling of being rescued, (well, maybe a time or two since then) but it’s a feeling that swells the heart. As Jake made his low pass over me, he tipped his wings in greeting. I am not sure about this, but I bet the grin on my face behind the camera, was wider than that of his, (through the window of his plane) although I could see his usual broad smile.

He made a wide bank down river and came straight in for a landing. He preceded Clint by several minutes, and we had coffee going by the time Clint touched his aircraft to the ground.

It was a great reunion, the success of a hunt, the promise of survival, I don’t know that they felt it, but I sure did.

The colors in the fire of the night before were now so insignificant that I really didn’t think about them for more than a year… but I am getting ahead of my story here so let’s go back to the gravel bar.

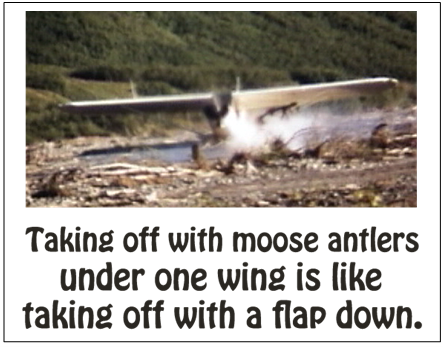

We loaded Jake’s plane as heavy with moose meat as we dared, he had more power than Clint to get back off the ground, but he also had the massive 63” moose antlers secured to his right wing, which was of some concern, because it would be like taking off with one flap down.

The takeoff was quite dramatic, I was no less than amazed when he reached the end of the gravel bar a hundred yards down river, and then continued out into the river before turning around for his take off? There he was with his wheels submerged in the river as he pulled the throttle back, putting power to the engine. Holding on the brakes, it almost lifted the tail out of the water and blew a visible vapor of water down the river behind him. When he released the brakes and the wheels began to roll, the bobbing and weaving of his wings indicated the large boulders, he was moving across on his way out of the stream.

When he reached the edge of the dry gravel bar the power of the engine was already thrusting the plane forward and he came down the gravel bar at a good rate of speed, he didn’t look at us as he passed, and we were standing clench jawed ourselves waiting for him to become AIRBORNE.

The river was fast approaching at the upper end of the gravel bar, yet his wheels were still on the ground, but as quickly as the dry ground disappeared so did his wheels from the earth, spinning freely out over the water. There were still a few tense moments as he pivoted up into the sky, and we waited for him to complete his bank and level off for his trip back to Kodiak. Then it was our turn.

It is said that, “Ignorance is bliss.” And that assumed true, I was in shear bliss on this trip. It had been a learning experience from the time my thoughts had questioned Jake’s sincerity when he asked me if I wanted to go moose hunting. There was much more I didn’t know: Such as using a 300 Savage rifle to hunt moose, and just thinking any rifle could kill anything. The wasted efforts in cutting the windpipe out of an animal you are about to butcher. The storm of which I was unaware, and now I didn’t fully realize the risks that Clint was likely contemplating in his mind. Clint did not bother to go into any details about the fewer horsepower his engine produces, the questionable length of our runway, the weight of the extra moose meat he had accepted, (to help lighten Jake’s load) or even my dead weight on board, although I felt very much alive at the time.

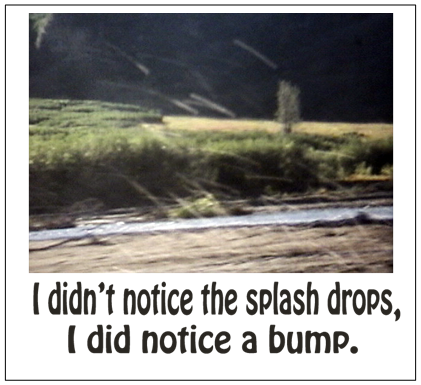

Just like Jake had done, Clint pulled his aircraft well out into the river at the far end of the gravel bar. However, it is a different sensation in ‘being there’ than observing it from a distance. Feeling and hearing the boulders grind and bang against the struts of the plane as it forces its way into the stream. The shuttering of the fuselage and deafening roar of the engine as it struggled through the drag of the current to make a turnabout. Once in position for takeoff, the engine volume increased again, as Clint powered it up to full throttle. I could sense the releasing the brake, as we bobbed and weaved across the boulders as I had seen Jake do. Not surprising to anyone who knows me, I was taking pictures out the side window during takeoff. Knowing this will be my last memories (documentation) of an area I would want to remember.

I was aware of the time we spent taking off, (although concentrating on pictures) I did not see the splash in my viewfinder. I remember how close Jake had been to the end of the island before pulling up. However, I again relaxed as I felt us lift off into the air. A slight bump, only to bounce one more time skyward. I had no feeling of danger, just the realization of experiencing it.

Clint wasn’t in any hurry to get back to Kodiak, so he flew me over to see the McNeil River Falls, which wasn’t far away. If you have seen pictures of bears catching salmon as they jump up some falls, there is a good chance they were taken along the world-famous McNeal River.

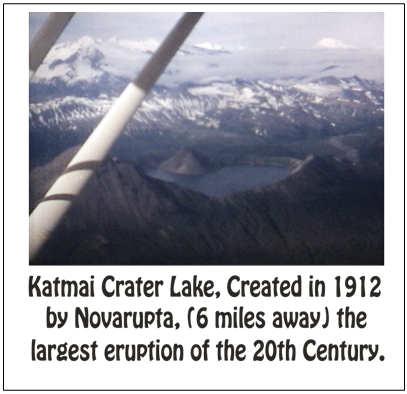

We also flew over Katmai Crater Lake, (see insert to left). Novarupta exploded, blowing 30 times the amount of material that was blown into the air by Mount St. Helens, leaving “The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.”

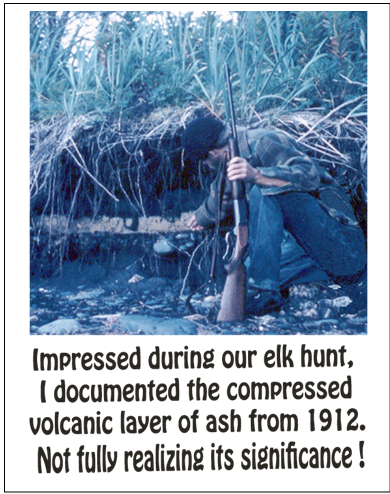

It deposited 12” of volcanic ash on Kodiak (and Afognak – see insert to right) collapsing many buildings on Kodiak.

I had just been thinking last night, that the power of nature is awesome in her silence; I would not want to be any where around when she is in a rage!

It had been an interesting tour, and I thank Clint for taking the time to do it, but it was now time to make our direction for Kodiak.

As we approached the Kodiak airport for a landing, it seemed like it had been an eventful trip, but not a dangerous one. Once we touched down, Jake and Rappid were waiting at the revetment, ready to help us unload. Rappid told me about the large storm system that he had been watching all night. “If that low pressure had have moved further east and settled in along the peninsula sooner, you would still be over there and maybe stuck for two weeks or more; I have often seen those big storms do that!” As Rappid was telling me this, I was also listening to Clint’s conversation with Jake about our take off. He said, “We barely made it out! I lifted off just as I ran out of gravel bar, but I didn’t have enough power to stay up, and when we came back down into the river, luckily we bounced back off!”

With all this going on, there’s little wonder I again placed little significance on the colored flames that emanated from the fire the night before, until over a year later when Rappid told me of his moose hunt on the Douglas River.

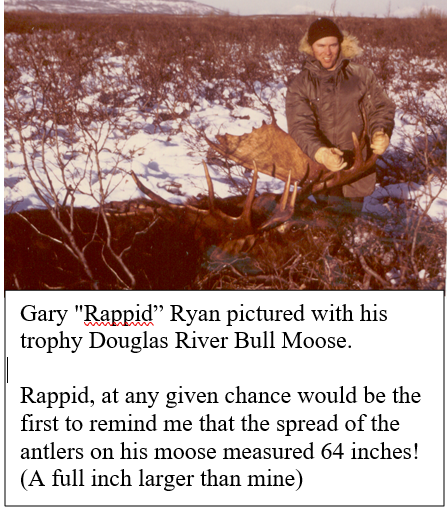

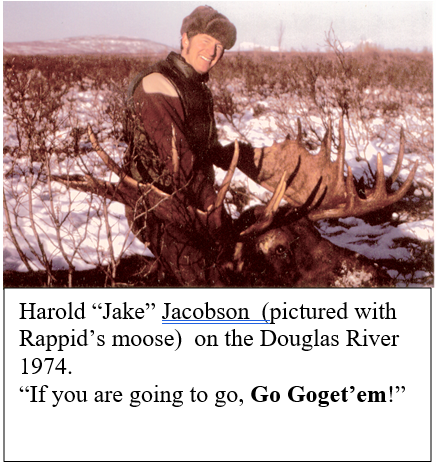

It was Early November 1974 when Jake flew Rappid over to the Douglas River for a moose hunt. The temperatures hovered near zero, and the available light was nowhere near what I had been enjoying while basking in temperatures ranging in the 50’s during those long September days of the previous year. Like on my hunt “Go Get’um” airways, went and Got‘em! Rappid still Braggs about the fact his bull had a 64-inch spread, a full inch larger than mine! (Who says size doesn’t matter?) However, if my bull had been given another two months to grow, he would have been at least two inches larger, I’m sure!

The following is an account of Rappid’s experience:

“We had finished hunting, loaded the plane with about a third of the moose meat, and we were in a hurry to get back to Kodiak, since it was getting late in the afternoon and we had to cross the strait (Shelikof) before dark. I had a large hunk of meat (part of a hind quarter) on my lap as we took off. The engine was not fully warmed up and coughed. We had just got off the river and were about 200 feet up. The plane tilted to the right, and looked as if it was going to go nose into the riverbank. Jake controlled it enough so that the trajectory of the plane flattened out, and we hit straight on into the alder trees along the bank. I was not nervous, until after the crash my heartbeat went up, but I was amazingly calm during the time we were going down. I was sure nothing bad would happen to me, and it was like watching a movie.

The river was frozen. We got out and saw the plane was tore up, fabric off the plane and the prop was bent etc. We went to the moose about a quarter mile and got the heart. We had survival gear, pitched the tent. I do not know if the ELT, (Emergency Locator Transmitter) was activated on impact, there was nobody around to hear it. Jake took it and put it in his pocket to save the battery.

We made a fire; it burned down to the ground, through about 18 inches of snow. As we were cooking the moose heart, we noticed some colors coming from the fire, something we had not noticed until it had burnt all the way to the ground. In spite of our perilous situation the fire added much comfort, we ate the heart from the moose, and it was good. Then we went to sleep. That night we were awakened by the sound of a C-130 flying overhead from the coast guard base on Kodiak. Jake activated the ELT, and we prayed they would hear it.

Next day, we made a fire and waited. Then we heard a helicopter in the distance. We had a nice signal fire burning, which had some colors to it. It was beginning to snow and visibility was dropping, which made our greatest fear that the helicopter would not find us today, so I took off my boots and threw them upon the fire (Tracker says, “don’t try this at home kids”).

Along with the expected large column of black smoke to my amazement the fire increased in a rainbow of colors. The sound of the Coast Guard Helicopter became louder and louder they had spotted our signal fire!

I got one boot out of the fire and put it on (it was still smoking) the other one was toast, so to speak. The Coast Guard guys were great…allowed us to pack our rifles in the helicopter (against regulations) but said no to any of the meat. I was wearing one boot and one boot liner; I am sure they took notice.

Hearing Rappid’s story, I recalled the uniqueness of my fire in September of the previous year; I told him of the “colored flames” I had been witness to. We became curious as to why the Douglas River area seemed to be unique to this phenomenon, and Rappid did some in-depth research of the area. He found that the Douglas River area is rich in minerals, in fact considered one of the most highly mineralized areas in the state of Alaska! We surmised that the Alder woods growing process somehow extracts some of these mineral deposits from the soil, and impregnates them into the aging rings. As this wood burns it releases colors of greens, blues and pinks back in to the atmosphere, and it maybe more than coincidence that the colors, which are released, are the same colors seen in the tributaries that feed the Douglas River drainage.

The effects of fire on certain minerals really came to light when Kent Wayment, (a friend where I worked) told me about colors he had seen in a fire while burning copper. Knowing copper was one of the most prevalent minerals in the Douglas River area, it was easy to make some connection, and we were further amazed of the effect when rubber was added with the copper (the boot effect?). The result is like Alder wood on steroids! This combination allows a normal campfire to produce similar colors as in the flames of a much larger fire in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

If you have ever seen the dancing reflections of color from one of these fires, past or present, then you have been witness to “An Ora Borealis”, some say “it is spiritual.”

Many reading this story would not otherwise know that my given middle name is “Ora” and in high school my friends often used my middle name, knowing it would add a little embarrassment. I would like to dedicate this story to Joshua Jacob Caleb Ora Westley, my nephew who shares the namesake, (Ora) and always enjoyed hearing Bears Butt’s version of this story.

I consider it an honor when friends share this story, and any time you share it around a fire: Jake, Cyclone Genesis, Rappid and I, (Tracker) will all be there with you!

Altered Wood

Bears Butt named it, “Altered Wood” and as far as I know there is no ‘right’ way to prepare it. There may be a best way, but it would only be coincidence if that were the way I have been doing it all this time.

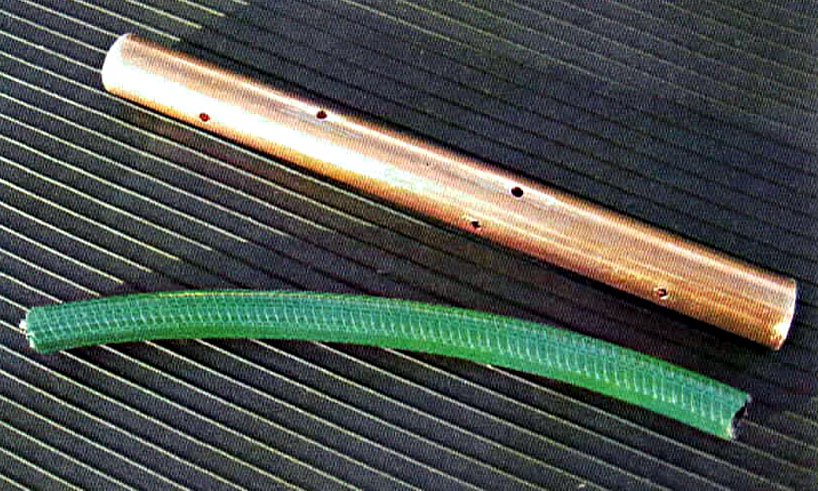

I use on foot (12″) of one inch (1″ diameter) copper pipe. I drill a few holes along the pipe to allow some circulation. I then take a one-foot length of vinyl hose (the cheap kind) and insert into the copper tubbing.

Once the outdoor (Camp) fire is well established with a good bed of glowing embers, I add one piece of “Altered Wood” into the embers under the burning wood.

CAUTION: I use long thick (welding) gloves anytime I hand the copper tubing putting it in or taking it out of the fire to protect from burns.

CAUTION: The copper tube can be very hot even when it doesn’t appear to be. It is very dangerous at this time; so protect if from those who are unaware of this danger. Never leave it unattended along side the fire.

I have never noticed a burning rubber smell from these fires, but I am sure inhaling the fumes would not be good for you, so only use the altered wood outdoors, sit back and enjoy the fire from a distance.

I hope that this information adds nothing but color, enjoyment and warmth to your camp.